If you’ve read the About section of my blog, you may have noticed that one of my main goals for the blog is to highlight interesting research and describe it in a way that non-linguists can understand. I have previously alluded to some research, for example, in the sound symbolism post. Today, however, I will dedicate the entire post to Dr. Katherine Kinzler’s 2009 paper, “Accent Trumps Race in Guiding Children’s Social Preferences.” If this post interests you, you may want to take a look at my previous post on language discrimination.

In previous literature, psychologists have already established that children care a lot about gender, race, and age in choosing friends. Children who are the same (or close) in these areas are more likely to become friends than children who differ in a category. For example, a white female child of age 6 would prefer another white female child of age 6.

Dr. Kinzler, of the University of Chicago Psychology Department, wanted to see whether language was a factor as well. She came up with simple experiments that tested for whether children would want to be friends with children who both spoke a foreign language (which the children in the study did not understand) and used foreign-accented speech (which they did).

For Experiment 1, children were asked whether they would rather be friends with a white boy who spoke American English or a white boy who spoke French. Unsurprisingly, they chose to be friends with the child who spoke English. When choosing a friend, it is certainly advantageous to be able to understand that friend.

In Experiment 2, children were asked to choose between a boy who spoke French and a boy who spoke English with a French accent. When the children were asked whether they understood the French speaker or the French-accented speaker, the children overwhelmingly chose the French-accented speaker. However, when asked whether they would rather be friends with the French speaker or the accented speaker, the kids didn’t really care. If you speak with a French accent, you might as well be speaking actual French.

For Experiment 3, children were asked whether they would rather be friends with an African-American girl who spoke English with an American accent or a white girl who spoke English with a French accent. When race was pitted against accent, accent was chosen to be more important to the children than race in choosing friends; this is surprising, because race is considered to be very important to children in choosing friends, according to previous literature.

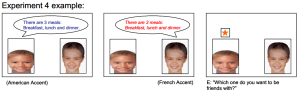

For Experiment 4, children were asked whether they would rather be friends with a white boy with an American accent or a white boy with a French accent. Children chose to be friends with the boy with the American accent as opposed to the child with the French accent. Again, this isn’t too surprising, as it agrees with the general “more like me is good” attitude established by the previous research.

Although race, gender, and age are robust factors in children’s friendship preferences, language seems to be important as well. Language and accent, as it turns out, are quite literally shibboleths for friendship among children. This means that, even for young children, language is a notable part of their lives. They therefore can, and do, discriminate on the basis of language. In fact, for these young children, language discrimination is more likely than racial discrimination. How much does this affect the social relationships we build? When you look back on your childhood friendships, did your friends talk like you?