“Like” has often been described as a filler. It’s a brainless way to fill space in a sentence, we’re told, and that its use as anything other than a comparative or a verb indexes a speaker as stupid or absent-minded. And while I could go on and on about how this interpretation is an arbitrary, prescriptivist point of view and that it has sexist implications, I am instead going to spend this post showing you all the ways in which “like” is actually quite meaningful outside of the standard, English-teacher-approved usage. I’m drawing many of these definitions and descriptions from the introduction to Chris Odato’s dissertation, “Children’s Development of Knowledge and Beliefs about English ‘Like’,”1 which is an interesting read in itself.

It turns out that “like” is in fact not a mindless filler, but instead has grammar and meaning as does every other part of speech. The following are innovative uses of like (not necessarily new, just outside current Standard English usage). Some sources claim that some uses may be over a hundred years old.

Discourse Like

There are two types of discourse “like”:

1. Like, he’s really trying to work on it.

2. It’s, like, a big deal.

The first example is one that occurs before a clause2 (discourse marker like) and the second example illustrates one that occurs within a clause (discourse particle like).

There are two theories for why people use “like” in this way. One argument is that discourse “like” is used as a “focuser”; it signals to the listener that the content of the following phrase is important. It has also been posited that discourse “like” can be a qualifier, meaning that the speaker is not sure about the truth of the content that follows the “like.”

Quotative Like

Quotative like is when we use the verb to be + “like” in place of “he said” or “she did this.”

1. And he was like “whoa!”

2. She was like [does interpretive dance]

This to be + “like” construction can only be used for direct quotes. For example, with the word “said”, you can say “She said that she’s coming,” or “She said ‘I’m coming.’” However, “like” can only be used with the second (direct) quote. So, you can say: “She was like, ‘I’m coming!’” but “She was like she’s coming” would sound pretty weird. Perhaps the fact that “She said ‘I’m coming’” sounds pretty strange outside of the context of written language might have created a need for a quotative that accounts for direct quotes, but I’ll admit that’s largely speculation on my part.

Approximative Like

“Like” is also used for approximating expressions.

1. She was stuck there for, like, three hours.

In this case, “like” is essentially a synonym for “approximately.”

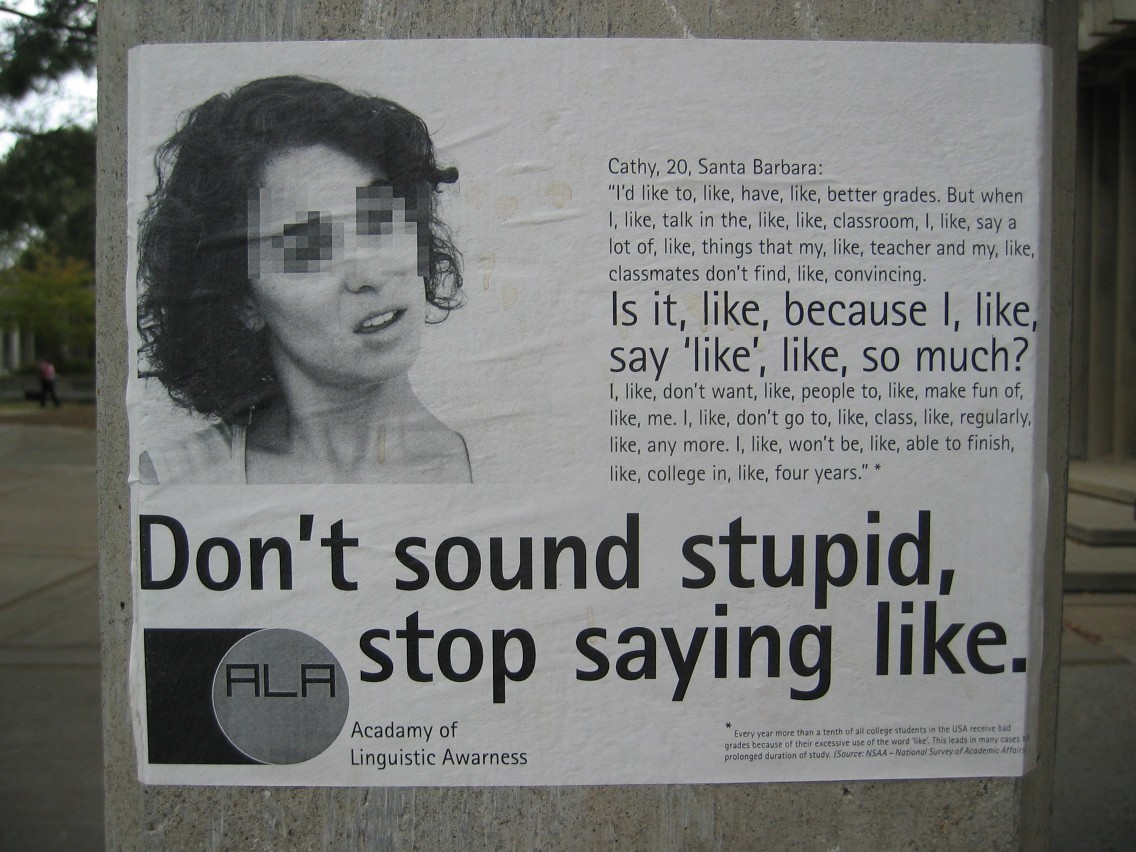

As you can see, there are real, meaningful uses for the word “like” in spoken language.. Many of those uses of “like” in the ad above are not something you’d hear in the real world. For example, “I, like, don’t want, like, people to, like, make fun of, like, me.” In what scenario would you hear someone say “make fun of, like, me?” Think about the way that sounds — would any of your friends legitimately say that? There is no need for a qualifier, because if people were making fun of you, you probably would not be unsure who it is they’re making fun of. And there’s no need for discourse like as a focuser, because you’re highlighting the fact that you get mocked, not that you are mocked as opposed to someone else. And there’s no approximative need — you are not more or less “you.” So not only is the ad insulting; it’s also just wrong. Although the people who made this ad may understand how “like” is used intuitively as native speakers; (many of them probably use it on a regular basis themselves), they manipulate the language and take advantage of its stereotyped role as a “filler” to create an exaggerated caricature of a young woman.

_____________________________________

1Unless specifically mentioned, this information all comes from that dissertation.

2A clause is very similar to a sentence. If you can state whether a string of words is true or false, then it’s a clause. For instance, if you say “It’s raining today,” you can say whether that statement is true or false. However, if you say “to the store,” we do not have enough information to be able to say whether it’s true or false.