This week, my research was featured on an episode of LingLab! Take a listen.

This week, my research was featured on an episode of LingLab! Take a listen.

Recently, the documentary Do I Sound Gay? was added to Netflix. I decided to watch the documentary and do a linguistically-informed review of the movie.

Do I Sound Gay? is a very personal documentary. The filmmaker, David Thorpe, starts filming as part of a project to sound less gay. He has just ended a relationship. His speech embarrasses him. His language is symbolic of his identity as a gay man in the US, and he targets it as the root of his self esteem issues. For Thorpe, like for so many others, language discrimination is a proxy for other types of discrimination, in this case homophobia. As interviewee Dan Savage puts it, it’s “the last chunk of internalized homophobia, is this hatred of how they sound.”

Thorpe consults his friends, speech pathologists, linguists, films studies researchers and celebrities. The film is more personal than scientific. All of the information about gay speech is presented through the lens of how Thorpe can sound less gay. Speech pathologists urge him to shorten his vowel sounds and use a falling intonation rather than a rising intonation in his sentences. Linguists Ben Munson and Ron Smyth discuss “s”, a well-known marker of gender and sexuality, and the fact that gay kids are more likely to be misdiagnosed with a lisp. Smyth discusses other patterns associated with gay speech such as a loud, released “t” and longer vowels.

In general, though, the linguistic details are peripheral to the bigger story: why do gay men want to sound less gay? How does our culture see gay speech? When Thorpe asks Dan Savage why gay men prefer partners who sound less effeminate, his response is “Misogyny.” The issues at the root of the conversation are about language and power.

Overall, as a linguist, I’d recommend this movie, just don’t expect it to be too scientific. But that doesn’t mean you won’t learn something.

There are many linguistic features that contribute to one’s gender identity (and the perception thereof). This post about resonant frequencies is the second in a three-part series of blog posts about what makes men and women sound different.

In the last blog post in this series, I discussed differences in men and women’s speech and how social influence as well as the acoustic reality of sexual dimorphism affects pitch. However, pitch is not the only aspect of speech affected by the size differences between men and women. As you can see from the diagram below, men not only have larger vocal folds but they also have longer vocal tracts (the “vocal tract” refers to all of the organs involved in speech, between the lips and the vocal folds), due in part to the fact that men tend to be larger than women and also because men’s larynxes lower during puberty.

As such, the acoustics of men’s voices are changed in ways other than pitch. Because the “tube” in front of an articulation (see my post on vowels and consonants for more information about articulation) is larger, other frequencies that make up the wave found will be lower, just like the pitch is lower when the vocal folds are larger.

Vowel differences between men and women are easily measurable but tend not to be easy to hear; our brains do an excellent job adjusting for the difference in vocal tract size in speech. Linguists characterize vowels using the first and second resonant frequencies of the vocal tract. Resonant frequencies are the frequencies at which an object will vibrate the most (i.e. be the loudest). Every object has a natural resonant frequency, and when that frequency is met with a sound at the same frequency, the result can be disastrous. Think of a glass being shattered by an opera singer: that happens because the singer sings at the the resonant frequency of the glass. Likewise, the Tacoma Bridge collapsed because the frequency of the sound of the wind was the same as the bridge’s resonant frequency. Vocal tracts, like all objects, have resonant frequencies, but these resonant frequencies can change because we can manipulate our articulators (anything we use to form speech, including the tongue, the lips, the teeth, the alveolar ridge, the velum, etc.).

via All Things Linguistic

The differences between the resonant frequencies of different sounds in men and women’s speech can be explained in part by size differences but, like pitch, can also be exaggerated in order for speakers to perform gender. There are two ways to create lower formant frequencies in one’s speech: to have a larger vocal tract, or to move the tongue back a little while speaking. One study found that children differed in their resonant frequency production as early as four years old, before any major differentiation in size between male and female children is observed.

Consonants, too, are affected by the size of the vocal tract. Think about the sounds “s” as in “Sam” and “sh” as in “sham.” The “s” sound is a higher-frequency sound than the “sh” sound, because the “s” is pronounced further forward in the mouth. The “s” sound is a major cultural marker of gender. When we hear an “s” pronounced further in the front of the mouth, we associate that sound with femininity, partially because it is higher frequency and gives the impression that the speaker has a smaller vocal tract. This fronted “s” is what non-linguists often refer to as the “gay lisp.” It’s not quite a “th” sound like a stereotypical (inter)dental lisp. However, it is pronounced closer to the teeth (where “th” is pronounced) than most “s” sounds, which are produced by holding the tongue very near the bony ridge behind the front teeth, known as the “alveolar ridge.” Conversely, an “s” pronounced further back, closer to the “sh” sound, will sound more “masculine.” It may also sound more rural to many American English speakers.

While these differences are mainly based on size differences, like pitch, they can be manipulated in order for speakers to perform a gender identity. These manipulations occur even while the vast majority of speakers are completely unaware of them. In the third installment of this series, I’ll talk about social differences between men and women that are not so easily linked to biology.

Feminist scholars have a term for the orientation of Western culture: androcentrism. It refers to a society in which men are at the center of the culture, and women and non-binary people are considered peripheral to the culture, which is inherently masculine. The androcentric model, in medicine, refers to the practice of placing the male body as the norm, and the female body as either abnormal or derivative of the male body.

Like every other field, medicine is affected both by societal influences and by the language resulting from those societal influences. Dictionaries are a good place to investigate these influences, in their role as authoritative guides on “correct” language usage. Victoria Braun and Celia Kitzinger conducted a study of 12 medical dictionaries and 16 English-language dictionaries, looking specifically at definitions of women’s genitals compared to men’s genitals. The study is new (well, 2001) but the cultural messages are old: women’s bodies are passive and men’s are active, women’s exist while men’s are functional.

In all of the dictionaries that Braun and Kitzinger studied, the definition of the penis was function-based. All of the dictionaries made some allusion to the penis’s sexual function and referred to it as an “organ.” By contrast, according to the Braun and Kitzinger, all of the dictionaries represent “the vagina as an open space, rather than as a body part adjusted for particular function.” Most used words like “tube” or “canal,” and many of the descriptions were location-based, relying on the existence of other body parts (like the cervix and the vulva) for the definition. The authors point out that most dictionaries left out any mention of the vagina’s active physical abilities, such as the ability to stretch.

The story is a little less bleak for the clitoris — if it’s even included, which is not the case for one of the medical (!) dictionaries — but only because it is “represented as a less developed, or smaller, form of the penis.” All of the medical definitions define the clitoris in terms of the penis, and only four of those dictionaries describe the penis as “homologous to the clitoris.” Because of its general definition as an underdeveloped penis, the main function alluded to in the definitions is the erectile capability of the clitoris.

Like the vagina, however, the focus of the clitoris is again on location. All but one of the medical dictionaries and 14 of the 16 English language dictionaries provide information about where the clitoris is located. Braun and Kitzinger quip that this information is “presumably included to help the reader solve the mystery of where a clitoris might actually be found.” This point of view seems to be based on the assumption that the typical reader will be a hapless straight man who only wants directions to the aforementioned genitalia but wouldn’t know what to do with them when he got there.

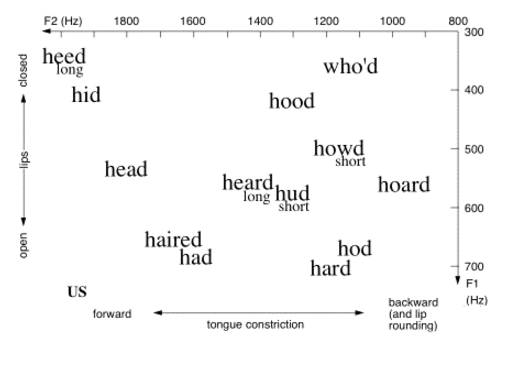

For the most part, linguists make assumptions about speech based on the acoustic information we get from the sounds made when speaking, as opposed to what our tongues are actually doing when we speak. We make plots and charts based on those sounds, then manipulate that information to visualize data in a way that is consistent with what the mouth is doing.

We can use this acoustic information to categorize sounds. For example, when we see certain acoustic characteristics, we can know whether a sound is a consonant or a vowel, or that it is a specific type of consonant or vowel. After all, we make the same judgments as speakers of a language when we hear a word: generally we only get acoustic information (along with a limited set of facial cues, such as lip rounding in sounds like “o” and the total closure of the mouth in sounds like “p,” “b,” and “m”) when we perceive speech. In the waveform below (a visualization of volume in speech), we can see that there are two consonants in red and two underlined vowels, just by the information we get about volume — consonants are formed with more closure, and therefore, less volume than vowels.

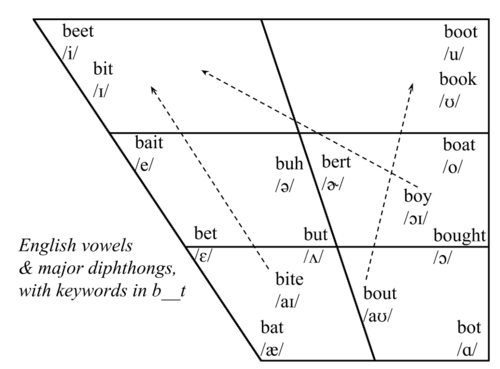

Vowels are a good example of how linguists use acoustic information to make judgments about how sounds are actually articulated. The following vowel plot is an attempt to show where vowels in each word are produced, where “F2” is an acoustic measure representing how front/back the vowel is produced, and “F1” is a measure of how high/low a vowel is produced. You can see (and feel, if you pronounce it out loud) that the vowel in “heed” is pronounced high and front in the mouth, whereas the vowel in “hod” is pronounced lower and further back.

Sometimes, though, acoustic information doesn’t tell us everything we need to know. An American “r” sound, as in both the beginning and the end of the word “rare,” will give us the same acoustic information no matter what. But if you look at “r” with ultrasound imaging, there are two very distinct ways of articulating that sound.

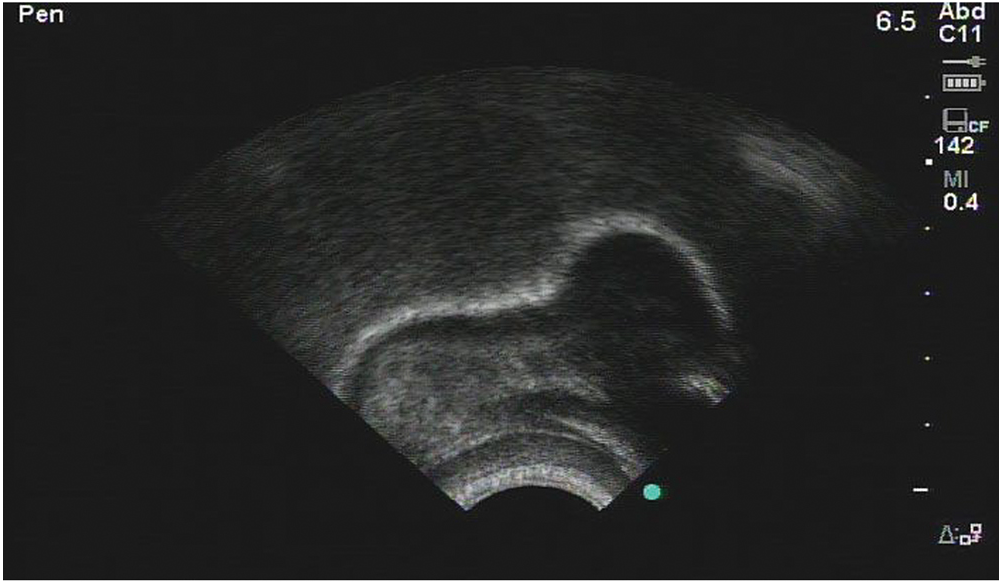

The first is what linguists call a “bunched r.” The ultrasound images below represent the tongue: the right side is near the tip of the tongue, the left side is the tongue root. Both are taken from Klein et al (2013).

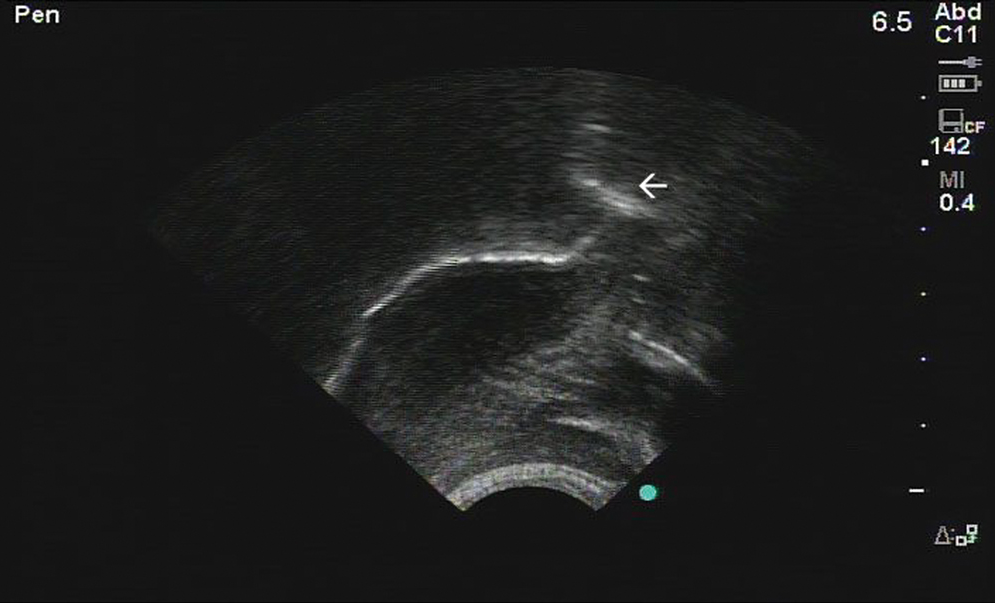

The second is what linguists call a “retroflex r” — the arrow is pointing to the tip of the tongue, which is curled backwards.

Despite two very different tongue shapes, the acoustic information for each looks almost identical, and there are no patterns of sex, region, class, ethnicity, or anything else that accounts for the differences in producing these sounds. Imaging techniques are the only way for linguists to know that some people produce bunched “r” and some people produce retroflex “r.” Both types of “r” are characterized by the dip in the purple line in the following spectrogram (which shows acoustic information, but we won’t get into the details in this post):

Linguists use articulatory imaging to make heat maps of the movements of certain sounds and to look for specific features — the top right square below measures the amount of “tensing” in the vowel “a” in “ban” (without getting into it too much, the “a” sound in “ban” or “bad” tends to be more tensed in front of “m” or “n” — compare the vowel in “ban” and the vowel in “bad”).

via Chris Carignan’s website

For all of the recent technological improvements such as the ones above, however, imaging used to be much better. Linguists used to look at speech via x-rays, which provided an amazingly clear picture of speech. Those methods are no longer widespread, due to the hazards of exposure to radiation for the amount of time needed to get images of whole words. For non-medical reasons, that type of risk is not acceptable. Now, linguists tend to use ultrasound or MRI rather than x-rays.

Older images do exist, such as this last image here:

via Christine Ericsdotter’s website

You can see the muscles working in tandem: the lips, the hyoid bone at the larynx, the tongue, and the velum above the back of the tongue, notably. This image represents the beautifully complex process that is speech, and even if we could get all the information that we need to answer specific questions about language from acoustic data, speech imaging gives us an insight and appreciation for speech that a waveform just doesn’t.

Once again, I thought I’d share with you some delightfully high-falutin’ linguistic terms for the most informal of speech. Here are three more things you didn’t know linguists had a name for.

Contrastive focus reduplication

She’s reading a book book, not an ebook.

Here, we repeat words in order to give them some sense of authenticity or intensification. In the example, an ebook isn’t considered a “real” book, at least not like a physical book. If you live in your college town and go to visit your parents, you might say that you’re going “home home,” to indicate that you’re not just heading back to your apartment but rather going back to your hometown, your “real” home.

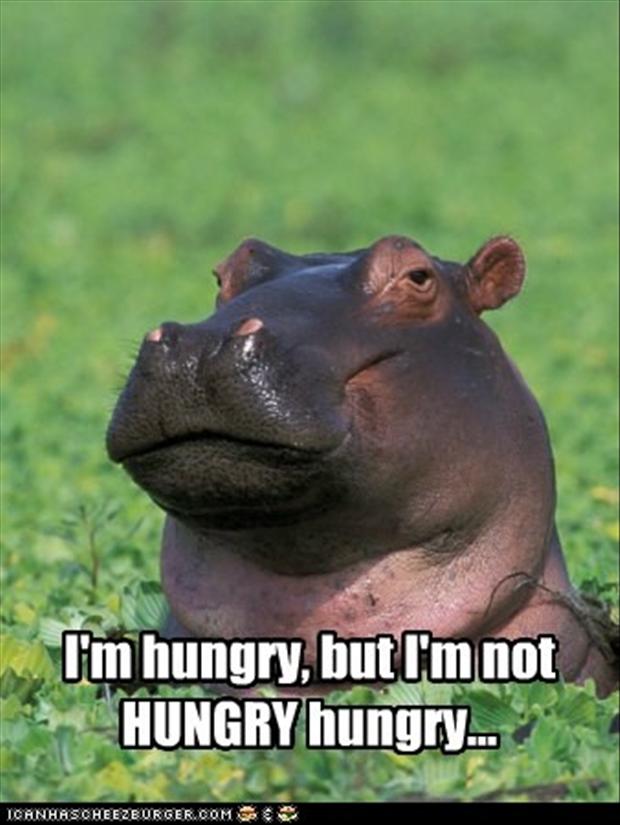

Contrastive focus reduplication can also be used for intensification of meaning, as in the meme below:

Shit substitution

Shoot the breeze → shoot the shit

Kicks and giggles → shits and giggles

Are you kidding me? → are you shitting me?

“Shit substitution” means replacing one word in an idiomatic expression with the word “shit”. This happens mainly due to the casual nature of both the word “shit” and the idiomatic expressions as well as the broad range of semantic categories the word “shit” can cover — from the verb referring to defecation, to an indignant reference to an abstract noun, to a fairly neutral informal synonym for stuff.

Fuck-based phrasal verbs

Fuck with

Fuck over

Fuck around

Fuck off

Fuck up

A phrasal verb is any verb which includes a verb and a preposition. Think of verbs like “keep up” and “freak out.” Fuck-based phrasal verbs are exactly what they sound like: phrasal verbs based on the verb “fuck.” “Fuck” is an incredibly versatile word in English, especially as a verb, as you can see from the diverse meanings of the examples above.

An interdisciplinary team of linguists, biologists and animal researchers at the University of Southern California is looking into the movement of octopus tentacles to illuminate how the human tongue moves.

Both the tongue and tentacles are part of a class of biological structures known as “hydrostats.” A muscular hydrostat is a part of an organism that is made of muscle and contains no hard structures (bones or cartilage). It moves by squeezing and stretching muscles against one another, rather than muscles being moved by bone. An elephant’s trunk is also classified as a muscular hydrostat. Whole organisms can also be hydrostats, such as the worm C. elegans, which the researchers also study as part of an NSF grant to investigate animal movement. The research team hopes that this research can provide insight into principles of movement across hydrostats, and that it may even have implications for research into muscular diseases like Parkinson’s.

Muscular hydrostats have more “degrees of freedom” than muscular structures that use bones to move them. This means that they are more flexible and move more freely, compared to, say, an arm, which can only move at the joints located at the shoulder, elbow, wrist and hands. This has important implications for speech, which requires many complex movements to form the different sounds of language; some distinct sounds in English, for instance, differ from one another by millimeters.

Iskarous and his team are interested in these degrees of freedom. “Octopus arms are capable of very non-rigid movements,” he says, “but they can also make their own rigidity, make their own joints, and can even walk on those joints.” Octopodes have increasingly become a topic of study among biologists; a recent discovery has found several expanded gene families in the octopus’s genome. However, the octopus is only recently a topic of study for linguists.

Tongues, too, can be either very flexible or rigid. In sounds like the “t” sound in English, the tongue back becomes rigid, and moves forward to make contact with the alveolar ridge, the bony ridge located behind the front teeth. The octopus uses similar principles of movement in its behavior in the wild according to Mairym Llorens Monteserin, a PhD student working with Iskarous. “Octopus have a really beautiful slapping motor pattern,” she said. When a fish threatens to enter the octopus’s den, the octopus pairs two of its tentacles together to form two “arms”, and holds them out in front of itself in a put-’em-up pose before deftly smacking the fish out of the way — employing the same rigidity that the tongue uses in saying “t” sounds.

Other sounds, though, require the tongue’s complex muscular movements and cannot be done with rigid muscle movement. For the English sound “l”, as in “bell”, the tongue must stretch to hit the alveolar ridge with the tongue tip and the soft palate with the tongue back, creating a sort of saddle shape if viewed from the side of the head; this stretching also makes the tongue narrower, allowing air to move around the sides of the tongue, which linguists consider to be a defining characteristic of the sound “l”. This sound requires hydrostatic movement in the tongue.

There are many linguistic features that contribute to one’s gender identity (and the perception thereof). This post about pitch is the first in a three-part series of blog posts about what makes men and women sound different.

I have previously written on this blog about the myths surrounding women’s language, encouraging readers to be skeptical of claims that men and women “speak different languages,” that women talk more than men, or that women are naturally better communicators than men. The way that men and women speak is in fact very similar.

So if men and women speak similarly, why do they sound different? If, for example, you get a call from a telemarketer, you can generally figure out the gender identity of the telemarketer without too much trouble. The main question for linguists (and others) who study gender is the following: which of these small but perceptible differences are biological, and which are social?

One of the first and most obviously biological differences between men and women’s speech is pitch. In one of his “Breakfast Experiments” for Language Log, Mark Liberman calculated the median pitch from two sentences read by 192 female and 438 male speakers, all native speakers of American English. In the chart below, the x axis represents median pitch in Hertz (frequency), and the y axis represents the proportion of speakers whose median frequency corresponds to that pitch. Most women (pink) have higher voices than men (blue). This is partially because men are normally larger than women (biologists call this sexual dimorphism), which means their vocal folds are larger. Thus, men have lower pitched voices — much like a violin is smaller and higher-pitched than a cello, even though structurally they are very similar.

These differences in pitch seem easy to explain based on sexual dimorphism , but in reality the picture is more complicated than that. There are several studies which indicate that pitch isn’t just about size. For example, a 1975 study found that pre-pubescent children have exhibited differences in pitch, even though their bodies are not very different in size because they haven’t gone through puberty yet. This finding indicates that children alter their pitch to imitate the adults around them, and fulfill the social expectation that boys have lower-pitched voices than girls of the same age, regardless of the biological facts of vocal fold size.

There are also many cross-cultural differences in pitch between speaker groups of the same gender. While it is the case in all documented cultures that male speakers usually have lower pitches than female speakers, there can be some surprising differences. For instance, the average pitch for a male speaker of English is 130 Hz, whereas male Swedish speakers have an average pitch more than 20 Hz lower (see table below). A 1995 study by Renee van Bezooijen found that Dutch women’s pitch was significantly lower than Japanese women’s. van Bezooijen hypothesized that women in Japan, with its strict gender roles for men and women, were expected to have higher-pitched voices in order to sound more feminine. van Bezooijen claimed that the Dutch women felt no such need because their culture is more egalitarian when it comes to gender roles.

From lecture slides from Dr. Rob Podesva, Stanford University

These findings indicate that what starts off as a biological difference from sexual dimorphism can be exaggerated based on social expectations. These social expectations are part of a concept known as gender performativity. Gender performativity is a term coined by Judith Butler, who theorizes that gender identity is bolstered by a continuous performance of individual acts. For instance, a woman may perform her gender by wearing a dress or wearing makeup. Certain aspects of speech are also symbolic of gender, and like clothing, these aspects change based on culture.

Pitch is one of these aspects. While pitch is a major factor in linguistic gender identity, it is not the only one. In the next installment of this special three-part series, I’ll talk about some other features that are different in the speech of men and women.

Eric Wilbanks is a second-year Masters student at North Carolina State University. He does research on corpus and network data from social media and Spanish linguistics, among other things.

As the nation gears up for another presidential election season, increased media coverage and attention is given to important “minority” voting groups, as candidates scramble to cater to populations which are (at the moment) extremely important to them—or at least to their vote. As presidential hopeful Marco Rubio demonstrates, the Latino/Hispanic vote is one of these desirable minority votes and Republicans and Democrats alike are attempting to demonstrate their dedication to and affinity with Latino Culture and Issues. In doing so, these cultural “outsiders” struggle to “correctly” define their target audience; are they chasing the Latino vote? The Hispanic vote? The Mexican vote? People place a great deal of importance on defining people in terms of their ethnicity or cultural heritage, often using these labels to delineate the boundaries between groups or place individuals into pre-determined boxes.

Grouping people by labels can be problematic, though, and definitions of ethnic or cultural identity are particularly personal and often touchy subjects. For Latinos/Hispanics in the US, the question is particularly difficult because the group defined by these singular labels is nearly 54 million individuals from diverse countries of origin, spanning four continents and numerous cultures, dialects, and languages. How can we possibly hope to represent the vast diversity of this group under a single, catch-all label? The majority of Latinos in the US prefer to answer questions of “where are you from?” or “what’s your ethnicity?” with their or their parents’ country of origin. Responses of “I’m Puerto-Rican”, “My family is from Belize”, or “I’m Dominican-American” are incredibly common and acknowledge the vast geographic and cultural divides which define this “group.” Additionally, this strategy allows for self-definition and acknowledges the fact that many people who outsiders would consider Hispanic really define themselves as American and don’t usually have a strong connection to their cultural/ethnic heritage in their daily lives. For some Latino/Hispanic groups, their preferred self-identification is Indigenous. As one indigenous Mexican woman declares, “I’m not Latina. Latino means genocide for my people […] I’m indigenous.” For many people, terms like Latino (originally referencing countries ruled by the Roman Empire) or Hispanic (referencing territories colonized by Spain) bring to mind the horrible genocides carried out in the Americas and are absolutely inappropriate for self-labeling.

For many in the US, however, Hispanic or Latino are the preferred terms. As Soledad O’Brien, a CNN correspondent, notes, there was once a strong regional preference, with the West coast leaning more towards Latino and the East coast towards Hispanic. However, this distinction has dissipated in recent years. For some, Hispanic brings to mind a sense of artificial “pc-ness” or a formal flavor. In addition to being an English word, the term Hispanic brings to mind a direct connection with imperial Spain, again problematizing the diversity within the group. One young Latino youtube commentator says that for him personally, Hispanic “sounds very academic, technical, it doesn’t really roll o the tongue, hi-spa-nic, plus it gave us the racial slur. On the other hand Latino [clear /l/, Spanish vowels] rolls off the tongue a lot easier, it’s in Spanish which is the language that most of us speak and overall I just think it sounds a lot cooler.”

In terms of his place in wider trends, it seems that this youtube commentator is right on the money. In the above graphic from CNN, we see that in Google trends, Latino is experiencing a steady rise while Hispanic is remaining relatively low, with annual spikes around National Hispanic Heritage Month. As an interesting side note, with the rise in popularity of Latino in recent years, some scholars have attempted to introduce the replacement Latin@. This orthographic innovation plays on the fact that Spanish marks grammatical gender, with Latino referring to a male or neutral entity and Latina referring to a specifically female entity. With the use of the at sign, these scholars hope to reduce female invisibility and promote gender equity. Unfortunately, there’s no natural way to pronounce the at sign and for now Latin@ remains restricted to academic writing.

When considering what label to use for Latino/Hispanic/Indigenous/Latin@/Dominican/etc… individuals, you might be confused at first. While Hispanic is viewed as a “PC” term, many Latinos view the term as inauthentic and foreign or reminiscent of their bloody colonial history. Latino might be seen as a more general term, but again many individuals disagree with the European centric view the term imposes and prefer instead Indigenous, country of origin, or simply American. Attempting to classify groups using a single overarching label will be bound to lead you into trouble. Obsessing over an individual’s ethnicity or cultural heritage ignores the fact that people are more than just their history and they define themselves in different ways in different contexts. While the search for the most “appropriate” terminology is important for census data or other similar applications, in everyday life the most personable and equitable way to determine a person’s preferred label is simply to ask them.

In 1996, the Oakland School Board in Oakland, California passed a resolution regarding a linguistic variety known as “ebonics.” Ebonics — a portmanteau combining the words ebony and phonics — is a dialect which linguists refer to as African American Vernacular English (AAVE). AAVE is a dialect associated with African-American speakers of English. This is not to say, of course, that all African-Americans use AAVE or that all users of AAVE are African-American, but it is a robust dialect among African-Americans in the US. The Oakland School Board declared Ebonics a language in order to raise its status, because languages have more prestige than “dialects.” The school board announced their goal of “maintaining the legitimacy and richness of such language… and to facilitate their acquisition and mastery of English language skills.”

This ideological position would have several practical implications — teachers with knowledge of Ebonics could possibly be paid more, funds would be used to teach all teachers Ebonics, and this knowledge of Ebonics would be applied in teaching students Standard English. Instead of treating Ebonics as a lazy form of English, it would be recognized as a legitimate form of language in its own right, with patterns and systematicity equal to those of Standard English. Students who speak Ebonics at home would not be required to learn Standard English seemingly by osmosis, but rather would be taught the specifics of the standard dialect explicitly.

The Oakland Ebonics Resolution was forward-thinking, progressive, practical, and scientifically and pedagogically sound. It addressed a major source of inequality in the school system and sought to lessen the Black-White education gap dramatically. But the public hated it.

The resolution elicited criticism from many, uniting political leaders from both the right and the left. It was denounced by civil rights leader the reverend Jesse Jackson, Maya Angelou, Joe Lieberman, the Clinton administration, and Secretary of Education William Bennett. Critics argued that we were dumbing down standards in our schools, and civil rights leaders worried that we were failing our African-American students by discouraging them from learning Standard English. Misunderstandings abounded, especially the notion that all instruction would be done in Ebonics. People worried that Ebonics speakers would be put in ESL courses.

In response to this backlash, the Linguistic Society of America passed a resolution in January of 2007. The largest meeting of professional linguists in the country agreed unanimously that the Oakland school board was correct in their decision and lent their support as language professionals.

The systematic and expressive nature of the grammar and pronunciation patterns of the African American vernacular has been established by numerous scientific studies over the past thirty years. Characterizations of Ebonics as “slang,” “mutant,” “lazy,” “defective,” “ungrammatical,” or “broken English” are incorrect and demeaning… the Oakland School Board’s decision to recognize the vernacular of African American students in teaching them Standard English is linguistically and pedagogically sound.

Linguists went to work trying to change the minds of the American public. They wrote op-eds, talked to journalists, did interviews on TV. They reached out to political leaders. As a result of this push to educate the public, Rev. Jesse Jackson changed his opinion and announced his support for the school board decision.

Misunderstandings about the Oakland Ebonics resolution are based on standard language ideology. Even 9 years after the decision, there is still animosity towards the decision and towards Ebonics/AAVE. However, from a linguist’s perspective, the resolution could have a world of difference for kids who struggle to learn Standard English because their home variety is seen as broken and lazy.