One thing that really grinds linguists’ gears is the constant, nonstop perpetuation of language myths by popular media. As in other sciences, linguistic untruths continually get written up and given a sense of authority by journalists who don’t know the first thing about the topic they’re writing about.

This type of reporting is especially irksome when journalists write about language and gender, because a LOT of the reporting reinforces existing gender stereotypes. This is the case especially in psychology and neuroscience reporting, but it also happens frequently in linguistics. Part of this is because there is a bias in being published as a scientist; no one is interested in a study that says “women and men are actually pretty similar.” This principle also goes for popular media, which is one of the reasons why the following three myths about the way women speak are so pervasive.

Myth #1: Women talk more than men do

When I read claims about the differences between men and women, I like to ask myself a couple of questions. As a rule of thumb, here are two good ones to ask yourself: 1) does this claim have anything directly to do with the anatomical (ahem) differences between men and women? and 2) does this claim conform to existing stereotypes about women? If the answer to the first question is “no,” then you have some reason to be skeptical — there’s a claim that the differences are biological, but there may be no direct evidence for such a claim. If the answer to the second question is “yes,” then there may be a motive for the journalist to support the status quo.

In the case of this particular myth, the answer to the first question is “no”, meaning we have some reason to be skeptical. In the case of the second question, I believe that this claim reinforces stereotypes about women. The idea that women talk more than men is nothing new. There are many proverbs about women talking a lot, and generally the underlying message is the following: women talk too much. The implication is that women should be quieter than their husbands. Some of these proverbs are hundreds of years old, and the current trend in popular linguistics and popular psychology books are only continuing the tradition.

The truth is that in many different social situations, men actually talk more often. This has been studied in “expert” talk shows, large-classroom style discussions with questions asked, and male-female face-to-face discussions. Only when the topic was very feminine-oriented (i.e. pattern sewing), did women speak more often. When women do speak, they are much more likely than men to do what linguists call “backchanneling,” which is a general term for things like “uh huh” and “mhm” and head-nodding that a listener does to show the speaker they are listening and to encourage them to continue. Next time you’re in a restaurant and you happen to be sitting near a (heterosexual) couple on a date, do a little eavesdropping. You might be surprised to hear who does most of the talking.

Why do we have these very strong, persistent misconceptions about how much women talk? One reason is the fact that women are what linguists call “marked.” “Marked” speakers are ones that are considered exceptions, and can sometimes get more attention when they do something. Men (and indeed, most privileged groups) are considered “unmarked.” Ask a friend to think about the following sentence: “The mail carrier brought the mail to our house.” Chances are, they pictured a white man doing the carrying, although the sentence does not specify the gender of the mail carrier. And you probably just pictured the friend in this scenario being male. Only when there are strong gendered assumptions about certain words (for example, “the nurse” or “the secretary”) are we more likely to picture an unspecified person as being a woman.

When women speak, they are noticed more often. In a subtle, insidious way, people notice when women speak because they may not think that women should be speaking. These feelings may not be conscious. Even many people who claim to be interested in gender equality might still feel this way. Reading an article, they may think “Oh yeah, my Aunt Martha talks way more than her husband Jeff!” Perhaps Aunt Martha is a topic of ridicule in the family, while Uncle Bill talks a lot and no one notices. Because Uncle Bill is male, he has the advantage of being unmarked, and therefore “normal”.

Myth #2: Women are better communicators than men

Let’s see how it fares on our questions: 1) This research has nothing to do with actual anatomical differences between men and women and 2) I’d say again, yes, this finding supports the status quo. This myth serves the purpose of putting women back in their rightful place: in a supportive, relationship-oriented role. On the one hand, it’s something of a consolation prize by those who want to seem progressive while enforcing restrictive gender stereotypes: men are better at leading, at science, at a lot of things that make them just perfect for high-paying careers in industry and politics. But you know what women are good at? Communicating. Intuiting. Emoting. Knowing what to say and when to say it, in order to keep the peace. They’re good at supporting those men. Men get to be interested in their own development, whereas women are other-oriented. It’s science. Sorry, ladies.

The problem (well, one of the problems) with this is that it’s hard to establish what it means to be “good” at communication. One way that neuroscience is used to defend gender differences is through the discussion of hormones. If you can prove that hormones are involved in a social behavior, you could make an argument that there is a biological basis for differences between men and women. One study linked the act of communication to the increased production of the hormone oxytocin in women. Journalists cite the fact that oxytocin is the hormone responsible for love and pleasure; the implication is that women enjoy communication more than men do, presumably because it is easier for them as women. Oxytocin has been linked to those feelings, and is generally considered responsible for women’s attachment to their babies directly after birth. However, as Mark Liberman of Language Log pointed out, the article failed to mention that the study also stated that oxytocin in the marriage context tended to signal relationship distress, meaning that the women could associate communication with a stormy period in their marriage. To quote Dr. Liberman: “Oops.”

Even if there were no directly conflicting information in the very articles cited by the neuroscience-defending-sexism brigade, the very idea of using hormones as evidence has been criticized by some. For example, neuroscientist Cordelia Fine has critiqued the hasty conclusions neuroscientists make based on the assumption that (prenatal) hormones are linked to brain structure and behavior. Neuroscience is a fairly new field, and there isn’t much information about how brain structure affects behavior, or how hormones affect that brain structure. Even the measurements used to measure prenatal testosterone, for example, are fraught with flaws — most methods have not been proven to be valid, and yet are cited as evidence of difference between men and women. One popular method for measuring testosterone is the digit ratio between the forefinger and the index finger. Although men tend to have longer ring fingers than their index fingers, and women tend to have equal length, there are many exceptions to this rule and no direct link has been established between testosterone and digit ratio. If we can’t even agree on how to accurately measure hormones, I think we have a lot of room to be skeptical of claims made on the basis of hormones alone.

Myth #3: Women use “like”, vocal fry, uptalk, and other “Valley Girl” characteristics more than men do

If you’ve noticed a pattern here, this has the same answers to the questions as the other two myths. From a linguist’s perspective, there is absolutely nothing wrong with “like”, uptalk, vocal fry, and “Valley Girl” speech in general. These characteristics are used in media to show that a character is like, a total airhead. Through our stereotypes, these have become linguistic proxies for identifying a teenage girl, and are usually used to show that teenage girls are not very bright.

But here’s the thing. Teenage girls are not the only people who use “like”, vocal fry, uptalk, etc. It is true that there is a great deal of evidence to suggest that most linguistic changes are led by women, so all of these features did originate with young women. However, in 2014, young women are definitely not the only people using them any longer. “Like” is used by older people as well, though not to the same extent. Not only that, but men are actually using “like” more often. Uptalk is becoming much more common among men as well.

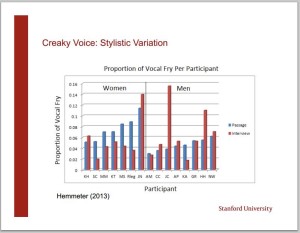

Vocal fry is considered a more recent phenomenon among women, and one that has had its fair share of vilification lately. It actually used to be associated with men in studies from the 1980s. While several recent studies have associated the feature with women in informal interviews, even more recent work (alright, mine) in Michigan has found that women and men don’t differ in their usage of vocal fry in informal situations. (Women did use more vocal fry in more formal speech.) The conclusion? Perhaps there’s a regional difference between Michigan and the other places where the studies were done (Washington DC and California) or maybe men are catching up to women in their usage of this feature, as they did with uptalk and “like.”

If you’re interested in hearing more about language and gender, or just the perpetuation of myths about the differences between men and women, I would highly recommend checking out The Myth of Mars and Venus by Deborah Cameron and Delusions of Gender: How Our Minds, Society, and Neurosexism Create Difference by Cordelia Fine.