Names are a source of fascination for many people. Perhaps it is because names are one of the most important linguistic aspect of our identities, and as such often evoke strong emotions. Perhaps it’s because there’s so much thought put into them; there’s hardly any other linguistic act that is as intentional as giving a name to a baby. We have all sorts of reasons for giving children certain names. We name them after people in our lives or book characters or celebrities. We may try to name them in a way that won’t make them conform too much but also won’t lead to bullying. We name them because we like the meaning of a name, or maybe we just like the sound of it.

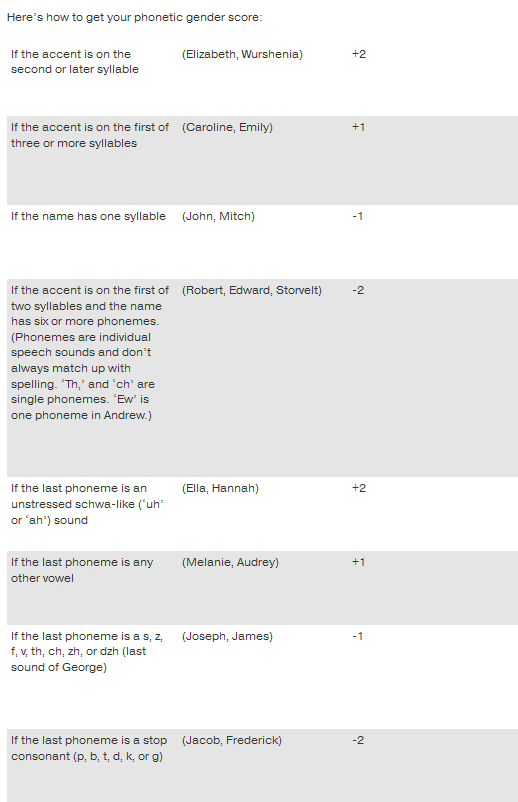

The sound of names is especially of interest to me, and I seem to be in some good company. There has been some very interesting recent research on the phonetics of names. One Mental Floss article by Arika Okrent asks “Why have baby names become increasingly female-sounding?” She includes a table of a system developed by Herbert Barry and Aylene Harper to determine what makes a name sound male or female in English, which I have copied here:

There are, of course, some exceptions to these rules, especially for names from certain other languages (for example, many Hebrew male names end in a schwa), but overall these rules are decent predictors of what will trigger each gender reading in English. And what Okrent found is that popular names for both boys and girls are skewing more female than they did in past years:

Why the change? Okrent posits that biblical boys’ names, those from Hebrew that end in a schwa, are having a comeback. 6 of the top 100 boys’ names end in a schwa, compared to zero in 1950. Names with six or more phonemes (individual sounds) are also falling out of favor with parents of baby boys; think names like “Howard” and “Edward” and “Leonard.” Girls’ names have also been becoming more feminine-sounding. Okrent believes that this is due in part to a decline in monosyllabic names like Gail and Joan, and an increase in names ending in vowel sounds, like Emily and Anna.

It turns out that not only are names influenced by generational trends like those Okrent describes, but they can also be affected by the political ideology of the parents. To hear about these tendencies in detail, I suggest listening to this Freakonomics podcast about names. Political ideology can also skew how “masculine” or “feminine” a name sounds. More conservative parents name their children, both boys and girls, with more “masculine” names. Liberals, by contrast, name their children with more “feminine” names across the board.

The more “masculine” and “feminine” names are described by Eric Oliver, the principal investigator of the study on this topic, as containing “harder” sounds and “softer” sounds, respectively. In many ways, this ambiguous description contains many of the rules from the Mental Floss article: conservatives prefer “harder” sounds at the end of names, like the consonants listed in the last two rules on Okrent’s chart. Liberals, on the other hand, prefer vowels like schwa and the “y” in Emily. According to Oliver, liberals also prefer names with softer consonants in them, like “l” as in “Milo” for a boy and “r” as in “Carrie” for a girl.

As an example, Oliver recommends taking a look at the names of two prominent politicians from either side of the aisle. Obama’s daughters, Sasha and Malia, have almost prototypical “liberal” names. They both are heavy on the vowels, ending in the schwa sound that garners you +2 lady-points in Okrent’s chart. Both contain “softer” consonants in the middle, “sh” and “l”. Now compare Sasha and Malia’s names to Sarah Palin’s five kids: Trig, Track, Piper, Bristol, and Flapjack.* All these names end in consonants rather than vowels. Trig and Track, the two boys, both have monosyllabic names that end in “hard” consonants, what linguists would call a “stop.” Stops are the most abrupt type of consonant.

It could be that these two findings are related. In general, conservatives tend to be more old-fashioned, and therefore they may be more interested in preserving some of the old, more masculine-sounding names. Liberals, on the other hand, may be more inclined to follow more recent trends. Demographically, the “millenials” — the people who are the most likely to be naming their children in recent years — tend to be more liberal than their older counterparts, even when those counterparts were the same age as they are now.

*Just kidding. Her other child’s name is “Willow,” but that would be a pretty “liberal” name, so I’ve excluded it from the example, and used this joke from Jon Stewart instead.